In a series of publications, David Lightfoot has made claims about the Triggering Learning Algorithm (TLA) for the acquisition of syntax. The core claim is that the TLA is an input-matching model which evaluates a grammar globally against a set of sentences heard by the child; this is then taken to show that the TLA is not a plausible or attractive model of acquisition. The purpose of this blog post is to show that this core claim is false.

What's the Triggering Learning Algorithm?

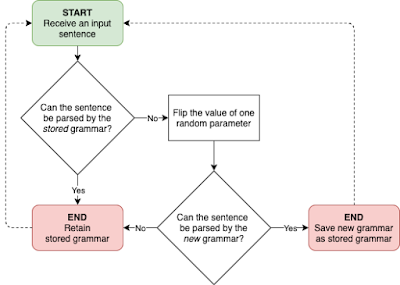

The TLA is an algorithm developed by Gibson & Wexler (1994) to characterize the acquisition of syntax by first-language learners. It assumes that the learning task involves setting a finite number of binary parameters: at any given time, the learner's grammar can be represented as just a vector of ones and zeroes. The flowchart below illustrates how it works, informally.

|

| Flowchart for a child hearing a sentence under the TLA |

The child receives an input sentence. This isn't just a raw string – rather, it's assumed that the child is able to extract certain syntactic properties unproblematically, so the input sentence, rather than "Mary likes motorbikes", would be something like "S(ubject) V(erb) O(bject)".

Lightfoot's criticisms of the TLA

"In being E-language based, these models face huge feasibility problems. One can see those problems emerging with the system of Gibson & Wexler (1994). ... [T]he child needs to determine which ... [grammar] his/her language falls into. That cannot be determined from a single sentence, given the way their system works, but rather the child needs to store the set of sentences experienced and to compare that set with each of the ... possible sets, not a trivial task and one that requires memory banks incorporating the data sets ... So if acquisition proceeds by Gibson & Wexler's TLA and there are forty parameters, then there will be over a trillion different data sets to be stored and checked, and each of those data sets will be enormous." (Lightfoot 2006: 76)

"Work in synchronic syntax has rarely linked grammatical properties to particular triggering effects, in part because practitioners often resort to a model of language acquisition that is flawed ... I refer to a model that sees children as evaluating grammars against sets of sentences and structures, matching input and evaluating grammars in terms of their overall success in generating the input data most economically, e.g. ... Gibson & Wexler (1994), and many others." (Lightfoot 2017a: 383)

"Gibson & Wexler['s] ... children are "error-driven" and determine whether a grammar will generate everything that has been heard, whether the grammar matches the input. ... There are huge feasibility problems for ... these global, evaluation-based, input-matching approaches to language acquisition, evaluating whole grammars against comprehensive sets of sentences experienced (Lightfoot 1999, 2006: 76f). ... [I]n order to check whether the generative capacity of a grammar matches what the child has heard, s/he will need to retain a memory in some fashion of everything that has been heard." (Lightfoot 2017b: 6–7)

"... involve the global evaluation of grammars as wholes, where the grammar as a whole is graded for its efficiency (Yang 2002). Children evaluate postulated grammars as wholes against the whole corpus of PLD that they encounter, checking which grammars generate which data. This is "input matching" (Lightfoot 1999) and raises questions about how memory can store and make available to children at one time everything that has been heard over a period of a few years." (Lightfoot 2020: 24)

"Gibson and Wexler take a different approach, but in their view as well, children effectively evaluate whole grammars against whole sets of sentences ... [W]hen they encounter a sentence that their current grammar cannot generate ... children ... pick another parameter setting, and they continue until they converge on a grammar for which there are no unparsable PLD and no errors. ... Gibson and Wexler's child calculate[s] the degree to which the generative capacity of the grammar under study conforms to what they have heard." (Lightfoot 2020: 25)

So has the TLA been saved, then?

- For certain systems of parameters, local maxima or 'sinks' occur – grammars which it is impossible for the learner to escape from (Gibson & Wexler 1994; Berwick & Niyogi 1996).

- Learning is more efficient if the Single Value constraint is dropped – that is, if the child is allowed to flip any number of parameters at once and jump to a completely different grammar (Berwick & Niyogi 1996; Niyogi & Berwick 1996).

- The system of parameters explored by Gibson & Wexler (1994) can be learned by a much more conservative learner who just waits for the right unambiguous 'silver bullet' sentences to come along (Fodor 1998).

- The TLA is very vulnerable to noisy input data: if the very last sentence the learner hears before fixing their grammar once and for all happens to be junk, the learner may flip to a different grammar, and "the learning experience during the entire period of language acquisition is wasted" (Yang 2002: 20).

- The TLA falsely predicts abrupt changes in the child's linguistic behaviour, and cannot capture gradualness or probabilistic variation (Yang 2002: 20–22).

- The TLA is dependent on a finite set of innate parameters in order to function; if this turns out not to be how syntactic variation works, then the TLA won't work either.

References

- Berwick, Robert C., & Partha Niyogi. 1996. Learning from triggers. Linguistic Inquiry 27, 605–622.

- Fodor, Janet D. 1998. Unambiguous triggers. Linguistic Inquiry 29, 1–36.

- Gibson, Edward, & Kenneth Wexler. 1994. Triggers. Linguistic Inquiry 25, 407–454.

- Lightfoot, David W. 1999. The development of language: acquisition, change, and evolution. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lightfoot, David W. 2006. How new languages emerge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lightfoot, David W. 2017a. Acquisition and learnability. In Adam Ledgeway & Ian Roberts (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of historical syntax, 381–400.

- Lightfoot, David W. 2017b. Discovering new variable properties without parameters. Linguistic Analysis 41, 1–36.

- Lightfoot, David W. 2020. Born to parse: how children select their languages. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Niyogi, Partha, & Robert C. Berwick. 1996. A language learning model for finite parameter spaces. Cognition 61, 161–193.

No comments:

Post a Comment