Adam Smith was an eighteenth-century Scottish Enlightenment philosopher and proto-economist associated with helping to lay the foundations of modern capitalism. His best known theoretical contribution is probably the invisible hand, and he’s lionized by right-wingers everywhere, especially in America – or rather a somewhat mythologized version of him is. One thing he is definitely not widely known for is his writings on language. But write about language he did! And, in particular, some of his ideas anticipate Peter Trudgill’s theory of sociolinguistic typology by 250 years.

|

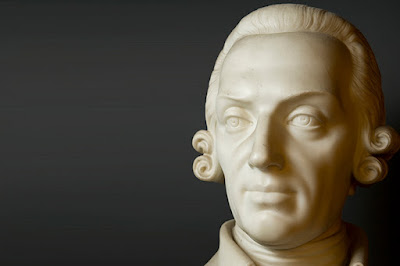

| Left hand side: the invisible hand. Right hand side: depiction of Smith. |

Smith observes that languages can be divided into types according to whether they have more morphology or less. To put it in somewhat anachronistic terms (though not, I think, inaccurately), in those languages with less morphology, the function of certain morphemes will instead be performed by separate words. So, for instance, in English, French and Italian, what’s expressed by case suffixes in Ancient Greek and Latin is expressed by prepositions, and what’s expressed by synthetic verbal forms is expressed by periphrases involving an auxiliary have or be plus participle (these are Smith’s examples).

This idea foreshadows the morphological typology developed by Franz Bopp fifty years later, as has been pointed out before. We can call the English-French-Italian type “analytic”, and the Greek-Latin type “synthetic”. But what hasn’t been commented on, as far as I’m aware, is how Smith relates morphological types to language contact. Here he’s worth quoting in full.

Language would probably have continued upon this footing in all countries, nor would ever have grown more simple in its Declensions and Conjugations, had it not become more complex in its composition, in consequence of the mixture of several Languages with one another, occasioned by the mixture of different nations. As long as any Language was spoke by those only who learned it in their infancy, the intricacy of its declensions and conjugations could occasion no great embarrassment. The far greater part of those who had occasion to speak it, had acquired it at so very early a period of their lives, so insensibly and by such slow degrees, that they were [p468] scarce ever sensible of the difficulty. But when two nations came to be mixed with one another, either by conquest or migration, the case would be very different. Each nation, in order to make itself intelligible to those with whom it was under the necessity of conversing, would be obliged to learn the Language of the other. The greater part of individuals too, learning the new Language, not by art, or by remounting to its rudiments and first principles, but by rote, and by what they commonly heard in conversation, would be extremely perplexed by the intricacy of its declensions and conjugations. They would endeavour, therefore, to supply their ignorance of these, by whatever shift the Language could afford them. Their ignorance of the Declensions they would naturally supply by the use of Prepositions; and a Lombard, who was attempting to speak Latin, and wanted to express that such a person was a Citizen of Rome, or a benefactor to Rome, if he [sic] happened not to be acquainted with the Genitive and Dative Cases of the word Roma, would naturally express himself by prefixing the Prepositions ad and de to the Nominative; and, instead of Roma, would say, ad Roma, and de Roma. Al Roma and di Roma, accordingly, is the manner in which the present Italians, the descendants of the antient Lombards and Romans, express this and all other similar relations. And in this manner Prepositions seem to have been introduced, in the room of the antient Declensions. The same altera-[p469]-tion has, I am informed, been produced upon the Greek Language, since the taking of Constantinople by the Turks. The words are, in a great measure, the same as before; but the Grammar is entirely lost, Prepositions having come in the place of the old Declensions. This change is undoubtedly a simplification of the Language, in point of rudiments and principle. It introduces, instead of a great variety of declensions, one universal declension, which is the same in every word, of whatever gender, number, or termination.A similar expedient enables men, in the situation above mentioned, to get rid of almost the whole intricacy of their conjugations. […]

Very similar ideas have been put forward this millennium by Peter Trudgill in his 2011 book Sociolinguistic Typology. There, the argument is that different language contact scenarios have different structural effects on the languages in contact. If the sociohistorical scenario is one of long-term societal multilingualism in which children are growing up as balanced multilinguals, then the languages in question are likely to become more (morphologically) complex by means of transfer of material. If, on the other hand, the scenario is a short-term one characterized by adult language acquisition, then (morphological) simplification of exactly the kind that Smith describes will likely take place. And the driver of simplification is exactly the same for Trudgill as it is for Smith: what Trudgill calls “the lousy language-learning abilities of the human adult”.

The parallel is of course not perfect. Contact-induced (morphological) complexification is a crucial part of Trudgill’s theory, but does not feature in Smith’s. And Trudgill and Smith differ on one very important point: the question of the overall complexity of a language. Smith writes (p470):

In general it may be laid down for a maxim, that the more simple any Language is in its composition, the more complex it must be in its declensions and conjugations; and, on the contrary, the more simple it is in its declensions and conjugations, the more complex it must be in its composition.

(By “composition” Smith has in mind certain aspects of syntax: in particular, the use of function words and the rigidity of word order.) In the 1950s, Hockett goes on record with a similar claim: “impressionistically it would seem that the total grammatical complexity of any language, counting both morphology and syntax, is about the same as that of any other”. This is a claim that Trudgill is at pains to disagree with in his book, describing it as “a propaganda ploy that was vital for combating the ‘some languages/dialects are primitive/inadequate’ view that has been widespread in our society” (2011: 16). On the other hand, the findings presented in Trudgill’s book do not really call the claim into question, since the vast majority of his evidence comes from morphology, and none of it from syntax (though he does cite work that fails to demonstrate a negative correlation between morphological and syntactic complexity).

Still, it’s fun to compare the two proposals, 250 years apart. As a final note: “naturally” is doing a lot of work in the chunky quote from Smith above! This underscores the need to actually establish how human language acquisition, and the language faculty, works (and ideally why it works that way) in order to have the full historical picture.

No comments:

Post a Comment